The Chicano Moratorium in East L.A. on August 29, 1970. Image: Sal Castro, Security Pacific National Bank Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

August 29, 2020, is the 50th anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium. A half-century has passed, but its spirit stirs again. What is it and how did it come into being? Why is it so important to Chicano people? And, how is it relevant to the demonstrations against racism and police brutality that are happening in Los Angeles right now.

The roots of the Chicano Moratorium grew out of the East LA Blowouts, walkouts organized by student activists and members of the La Raza community newspaper. The walkouts protested LAUSD’s attempts to pipeline Chicano students into manual arts schools or the Vietnam War rather than giving them the college prep and pathway to higher education they wanted and deserved. Clearly, someone didn’t want Chicanos to become lawyers and politicians. (For more on the East LA Blowouts, KCET has an excellent primer.)

One way to avoid being drafted was to go to college. Donald Trump—a rich, white man—received four deferments for college and a fifth for an injury, which his lawyer and fixer Michael Cohen told members of the House Oversight Committee was a lie. Cohen testified that when he questioned Trump on his deferment and injury, Trump said, “You think I’m stupid, I wasn’t going to Vietnam.”

Meanwhile, Chicanos were apparently good enough for cannon fodder, but not good enough to go to USC. This is part of a system of oppressive and institutionalized racism. Chicanos, like other ethnic groups and the poor, became meat for the grinder of the U.S. military.

The Chicano Moratorium was a demonstration organized by activists including the Brown Berets. It protested against young Chicanos being drafted into the Vietnam War, a hopeless conflict in which Chicanos had one of the highest mortality rates. On August 20, 1979, an estimated 20,000-30,000 people marched in East L.A., down East Third Street, Atlantic Boulevard, and Whittier Boulevard to Laguna Park. But a peaceful rally for Chicano rights was upended when law enforcement got involved.

The Chicano Moratorium on August 29, 1979. Image: Ken Papaleo, Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Descends

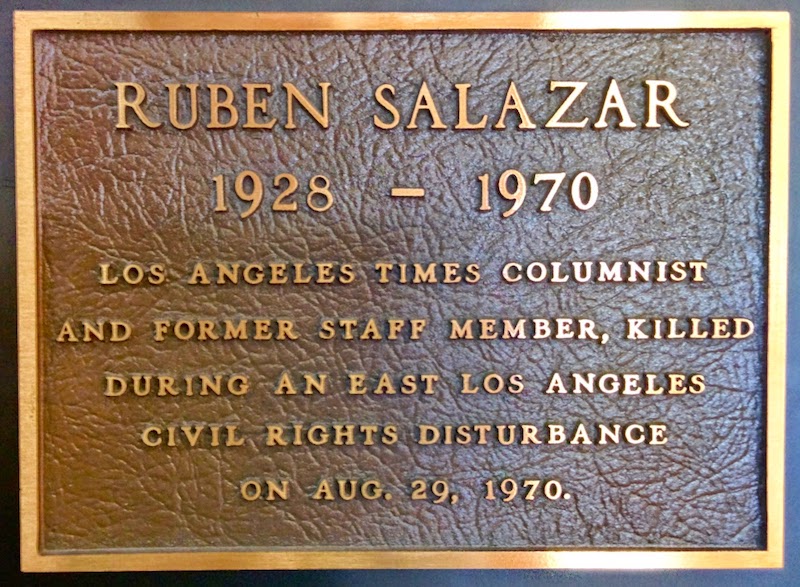

In any discussion of the Chicano Moratorium, you must consider the brutality of the LASD. They were the deputies who attacked the peaceful gathering at Laguna Park. They were responsible for the death of Los Angeles Times columnist and KMEX-TV news director Ruben Salazar, for whom Laguna Park is now named. There were three other deaths that day: Lyn Ward, a 15-year-old El Monte Brown Beret; Angel Diaz; and Gustav Montag. There were also numerous injuries and over 150 arrests.

Why did law enforcement descend on the peaceful march? According to the LASD, there was a disturbance at a nearby liquor store, The Green Mill. For no adequately explained reason, the LASD moved in towards the park full of Chicano families.

Things got violent. The LASD fired tear gas into the crowd. The crowd panicked and chaos ensued. Some threw the tear gas canisters back at the LASD. The LASD hit protestors with batons. Buildings burned.

This video, Requiem 29, is a collection of films of the Moratorium and testimony from the coroner’s inquest into Ruben Salazar’s death. The Chimalli Institute of Mesoamerican Arts put the footage on YouTube and it’s quite eye-opening.

In one particularly disturbing moment seen at the 9:25 mark, an LASD deputy clubs a young woman from behind at the base of her skull.

For some, the violence was nothing less than a pre-mediated assault on a proud celebration of Chicano identity. In the book The Chicano Generation: Testimonios of the Movement, Mario T. García features oral narratives from key figures, including activist and Chicano Moratorium organizer Rosalio Muñoz. Muñoz doubted a disturbance at a liquor store led to what transpired next.

Chicanos protest the arrest of four Brown Berets outside the LAPD headquarters on June 2, 1968. Image: Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

Surveillance, Speculation, and Red Lining

The Chicano Movement, like many groups seeking justice, was under surveillance, not just by local officials, but by the FBI and J. Edgar Hoover. This was the FBI’s policy of COINTELPRO aimed at putting a stop to the growing civil rights movement and resistance to the Vietnam War.

Journalist Ruben Salazar, a prominent reporter and activist who had clashed with local law enforcement before, had his own FBI file.

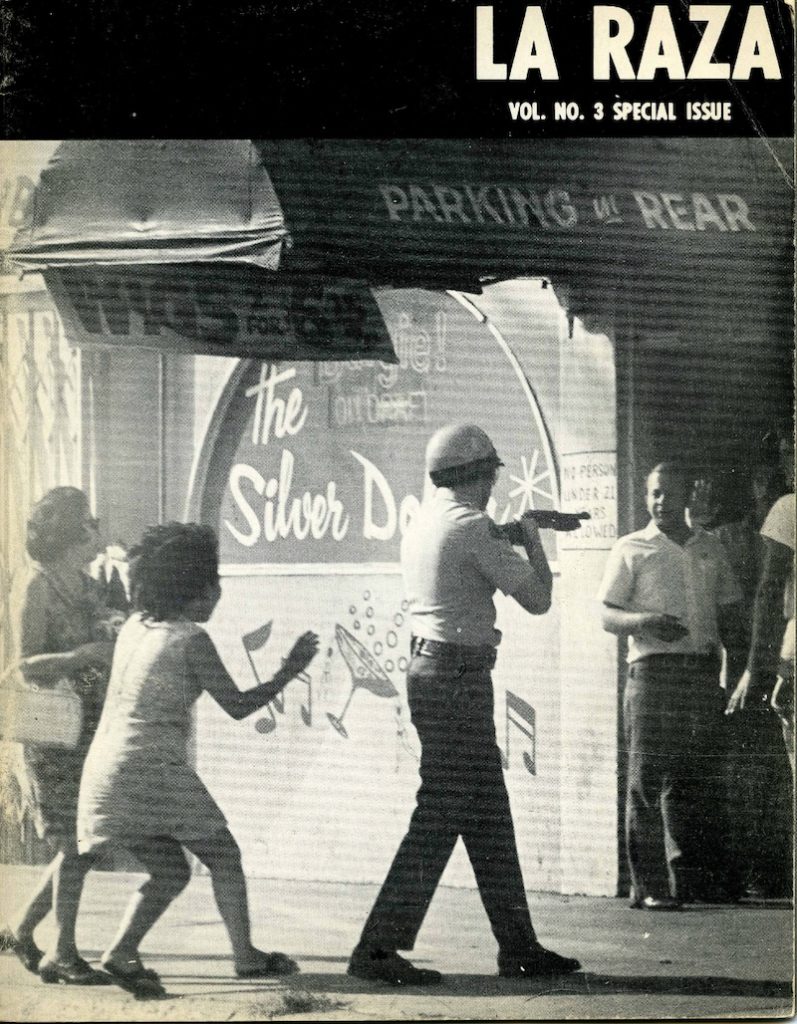

Salazar wasn’t killed at the protest, but in a small bar called The Silver Dollar, right around the corner from The Green Mill. He was relaxing and drinking a beer with journalist William Restrepo when Deputy Thomas Wilson shot a tear gas projectile through the front door. The canister fatally struck Salazar in the head.

Wilson fired a tear gas canister into a small, dark indoor area, through a curtain that blocked his view. According to Icarus Wong Ho-yin of Hong Kong’s Civil Rights Observer, one of the most basic principles in police training is that tear gas shouldn’t be used indoors. The Federal Flite-Rite projectile Wilson fired could pierce an inch-thick pine board. It carried a manufacturer’s warning stating it was only for driving out barricaded persons and wasn’t “to be used against crowds.” Wilson testified he thought he was firing a different type of projectile, which looked similar, but also that at the time, “it didn’t make that much difference to me.”

There’s been much speculation about whether or not Salazar was actually assassinated while the circumstances surrounding his death have remained murky. Deputies said they were responding to reports of armed men inside the Silver Dollar. That report was false. Restrepo said that LASD deputies had already been following them that day.

When the LASD finally issued a report on Salazar’s death in 2011—only 41 years later and after numerous requests to do so—it said there was no evidence to indicate Ruben Salazar was targeted. The City of Los Angeles quietly paid Salazar’s family $700,000 to settle a civil suit. Wilson was never charged. The idea that there was not, at the very least, misconduct involved in Salazar’s killing is absurd.

To this day, it’s unclear what really happened. L.A. Times reporter Robert Lopez has chased the truth for years, ultimately concluding that deputies just didn’t care who was in the bar and behaved in ways they wouldn’t have in a white neighborhood. “In the end, Salazar died from the very type of law enforcement abuse he was trying to expose,” Lopez writes.

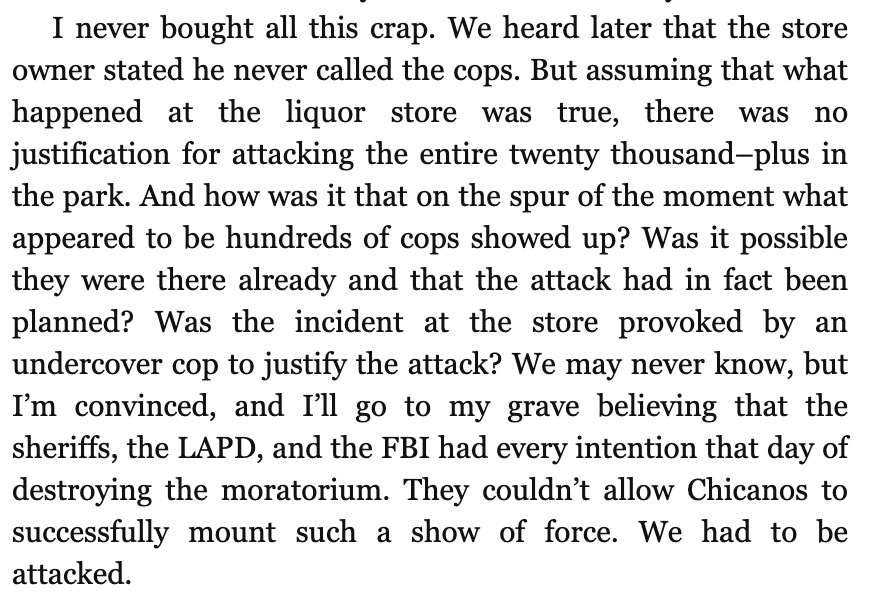

The journalist questioned at the inquest in the Requiem 29 video is Raul Ruiz of the newspaper La Raza. It’s notable that the official questioning him seems more interested in who broke windows and why the marchers had a banner referencing Che Guevara than investigating Salazar’s death. That is called “red baiting,” a logical fallacy in which someone tries to discredit another person by accusing them of being a communist, anarchist, or socialist. Here, it’s more about portraying Chicanos as scary communists than finding the truth. When L.A. Times reporter Hector Tobar reviewed those documents regarding Salazar’s death released in 2011, he noted that they were full of Nixon-era paranoia and established a clear “‘us vs. them’ mentality” in the department.

Tactics used by authorities and their proxies haven’t changed much in 50 years. Today, Black Lives Matter protesters are frequently called communists by commentators like Ben Shapiro as police use violence break up protests. The Guardian published a more accurate headline when covering recent protests over the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and others: “Protests about police brutality are met with a wave of brutality across the US.”

Police Violence, 50 Years On

According to the Youth Justice Coalition LA, the LASD alone has killed more than 330 people since 2000.

Andres Guardado, an 18-year-old Salvadoran American who reportedly worked as an unofficial security guard at a body shop in Gardena, was shot by an LASD deputy on June 18, 2020. He wasn’t in the same profession as Salazar, but there are similarities in what happened and how the LASD has chosen to react. Again, the information is conflicting and murky.

Law enforcement’s incomplete story is that Guardado was talking to someone in a car who was blocking a driveway near the body shop and that when he saw deputies arrive, he flashed a gun and ran. A deputy opened fire in a nearby alleyway, killing Guardado.

The Sheriff’s department put a security hold on the L.A. County Coroner’s autopsy results because, a department spokesperson said, “investigators wish to maintain the integrity of the investigation and premature release of information could jeopardize the case.” The family had a private autopsy conducted and Chief Medical Examiner-Coroner Dr. Jonathan Lucas defied the security hold to release the official findings. Both reports found Andres Guardado was shot five times in the back.

Law enforcement says they recovered ghost gun, a gun without serial numbers, that carried a high-capacity magazine. No one who knew Guardado thought he possessed any weapons.

In this interview with Memo Torres of LA TACO, the body shop’s manager Andrew Haney confirms that Guardado worked there and was talking to two women when LASD deputies approached. He said they immediately drew their weapons, which caused Guardado to run. He recounts that Guardado ran only to the end of the alley between the two businesses and then knelt and put his hands up. After he surrendered, one deputy shot him. Haney further states that deputies destroyed the business’s security cameras and confiscated the DVR without a warrant, but returned with a warrant later “to cover themselves.” Haney expanded further here.

But when speaking to KTLA, Haney was curt and not as open. He claimed that Guardado didn’t work there and that he just “hung out,” despite living about 15 miles away in Koreatown.

It’s been two months without answers. The deputies weren’t wearing body cams; those won’t roll out until October 1. The most we have, as of the latest update from the Sheriff’s Department, is a clip from a security camera across the street that doesn’t show the shooting.

Two deaths of Latino men separated by 50 years, one a distinguished journalist under surveillance and one an 18-year-old student working multiple jobs to make his way in the world. Both were killed by an LASD deputy under mysterious circumstances with little to no explanation. Neither man took any actions worthy of lethal force.

David Diaz has lived in East L.A. all his life. His great-nephew Paul Rea, 18, was shot and killed during a traffic stop in East L.A. on June 27, 2019. He describes the connection best, telling the Guardian that during the Chicano movements of the 60s and 70s, he felt like deputies were trying to make as many arrests as possible and that law enforcement had killed nine of his friends.

“The goal of sheriffs is to arrest as many people as they can and worry about it later. By arbitrarily arresting people and giving them records when they don’t deserve it, it has a negative impact on young people’s ability to succeed,” he said.

The powerful elements of structural racism have merely changed the emphasis of their tactics. They can’t keep Chicanos out of college anymore, but they can prevent those in certain neighborhoods from having the good record or self-esteem to reach for their dreams. They seek to crush the spirit and to cull those who shine too brightly. For anyone who might have trouble believing this is the case, surviving relatives of those killed by the LASD testified last year at a hearing before the Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission that deputies harassed them as they mourned their dead.

Rea’s sister Jaylene said patrol cars would drive by as they gathered at a memorial for him. After her grandmother tried to serve L.A. County Sheriff Alex Villanueva with a lawsuit to obtain police records, Jaylene Rea said deputies showed up at the family’s memorial that night and arrested her with excessive force. When she asked where she was being taken, they taunted her. When she got her phone back after her arrest, she said the videos she had taken of previous harassment had been deleted. She was able to restore them, but her allegations are chilling. Imagine someone arresting you, taking and going through your phone, and deleting evidence.

The Chicano Moratorium was about fighting for the future of Chicano children. How much has really changed in the ensuing 50 years? For the people of the United States to truly be free, all must be free. We must remember the struggles of the past to prevent the oppression and the tragedies of the future. That is the lesson of the Chicano Moratorium. Demanding your rights won’t be easy and the full victory might not be achieved in your lifetime, but pretending there isn’t a problem is no way to live. Pretending that there isn’t a problem won’t save you.

advertisements